We constantly hear about struggling automakers and game-loving people who can’t afford a Playstation 5 due to the lack of microchips around the world.

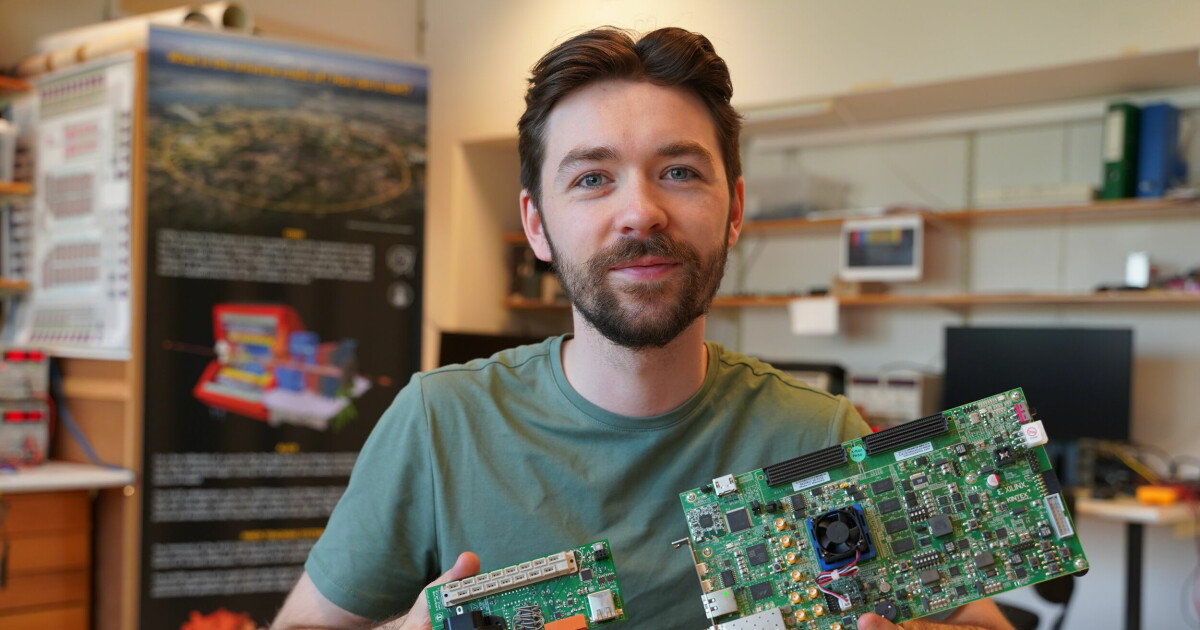

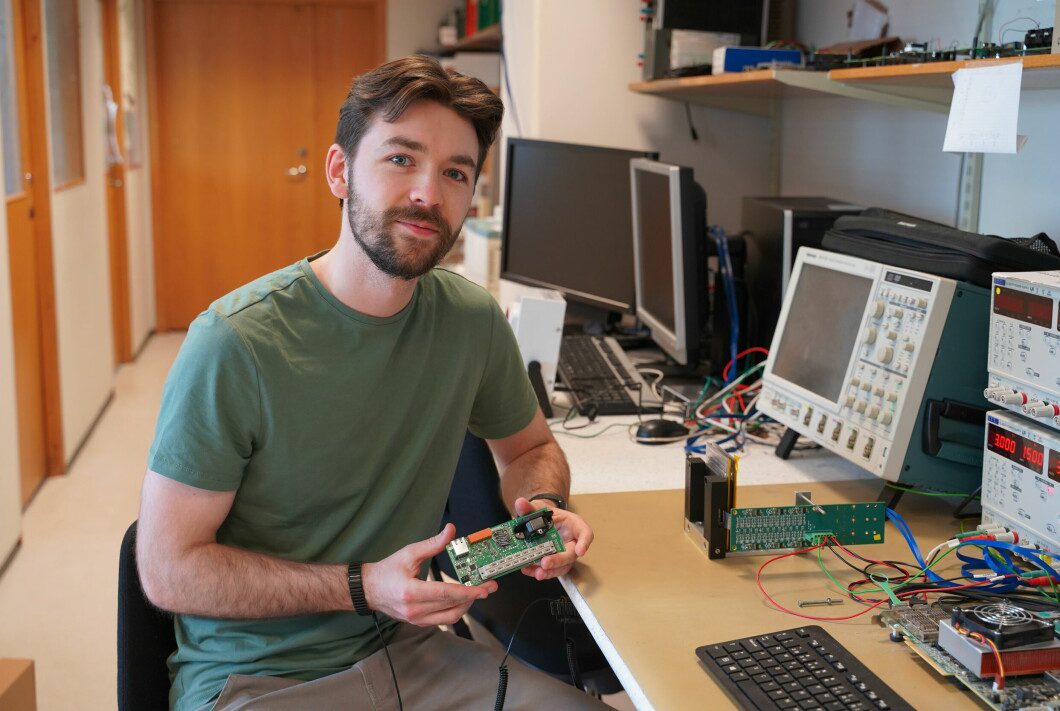

However, there are many who have felt the consequences, and one of them was microelectronics student Berger Olsen (24).

This spring, he began working on a master’s project at the University of Bergen.

The goal was to devise a technology that, in collaboration with other European researchers, would help improve radiotherapy for cancer.

There was only one problem – the chips.

Chips: Here’s the problem – a risky shortage of these microchips, which are also called semiconductors in technical parlance. Photo: Ivar Lid Riise/TV 2

Dramatic increase

When there was three months left of the project, and the deadline for his master’s thesis was approaching, Olsen had to order the microchips he needed.

– These tend to come quickly. This usually takes 1-2 weeks, and if we have to order from the US, it can take up to three weeks, says the student.

But this time, it was different. A pandemic, delivery delays and shortages of raw materials have increased the waiting time for microchips to at least seven months.

“Then we have to find other solutions,” I thought. The design had to be changed, and I simply had to find some other chips in the same area of use, says Olsen.

Change: The Birger Olsen (24) technology cannot be made as it was originally designed. The lack of microchips meant he had to make adjustments. Photo: Silje Olderkjær / TV 2

This is why there are problems

A master’s student from Bergen isn’t alone in chipping away at chips. For more than two years, the world has struggled with a shortage of microchips, and the cause is complex.

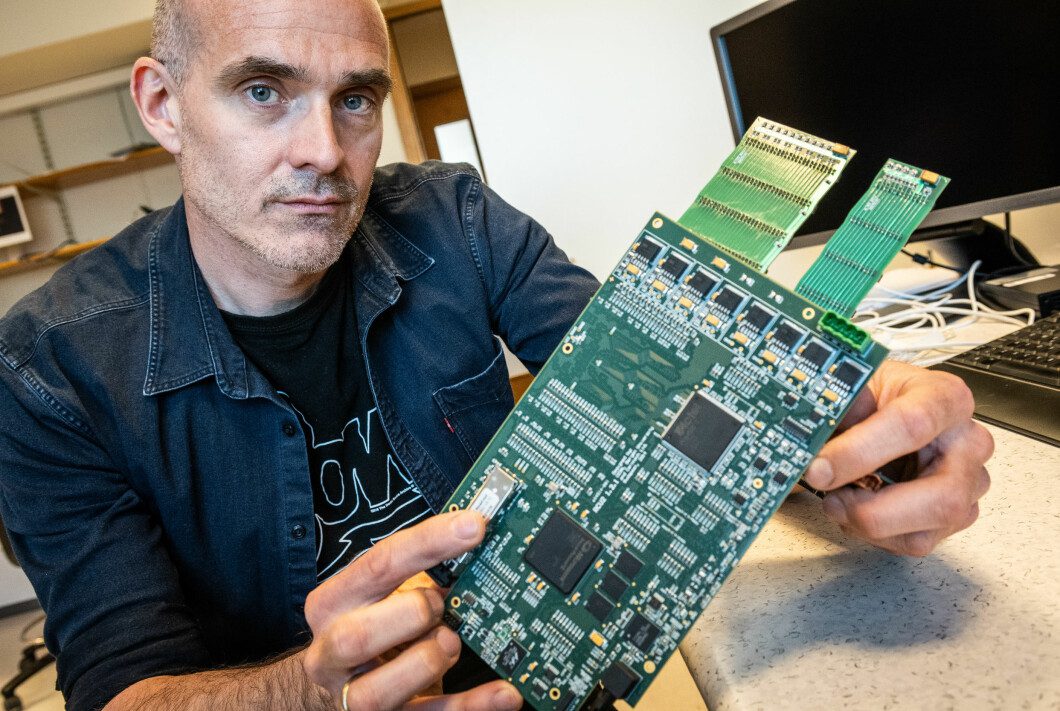

Professor Johann Almy works at the Department of Physics and Technology in Bergen Previously reported to TV 2 That the shortage is caused by a perfect storm.

Some of the reasons are the drought in Taiwan, the previous Trump trade embargo between the US and China, the rise of cryptocurrency and the coronavirus pandemic.

Now the epidemic is declining, but global delivery problems persist. The war between Russia and Ukraine does not help.

– We still feel it’s hard to get the ingredients. Even for those of us working on projects where we only need simple components, there is a very long turnaround time, Almy says today.

Waiting: Microtechnology researcher Johann Alme of the University of Bergen (UiB) says there is no quick fix to this problem. Photo: Ivar Lid Riise/TV 2

This is how long it can last

One A recent report from DeloitteShe asserts that there is still a huge shortage of microchips, or “semiconductors” as they are called in technical parlance.

Improvement can still be seen.

The report indicates that delivery problems may decrease in the second half of 2022. The scarcity will still be able to continue until 2023.

This is bad news for the auto industry, according to the financial advisory firm AlixPartners It lost $210 billion in 2021.

“Of course, everyone was hoping the chip crisis would subside more now, but unfortunate events such as the Covid-19 shutdown in Malaysia and ongoing problems elsewhere have made matters worse,” AlixPartners’ Mark Wakefield wrote in a press release.

Precision Mechanics: You are surrounded by high technology and precision tools when making microchips. Here from Renesas Electronics in Beijing, China. Photo: Mark Schiefelbein / AP

Waiting for the crystals

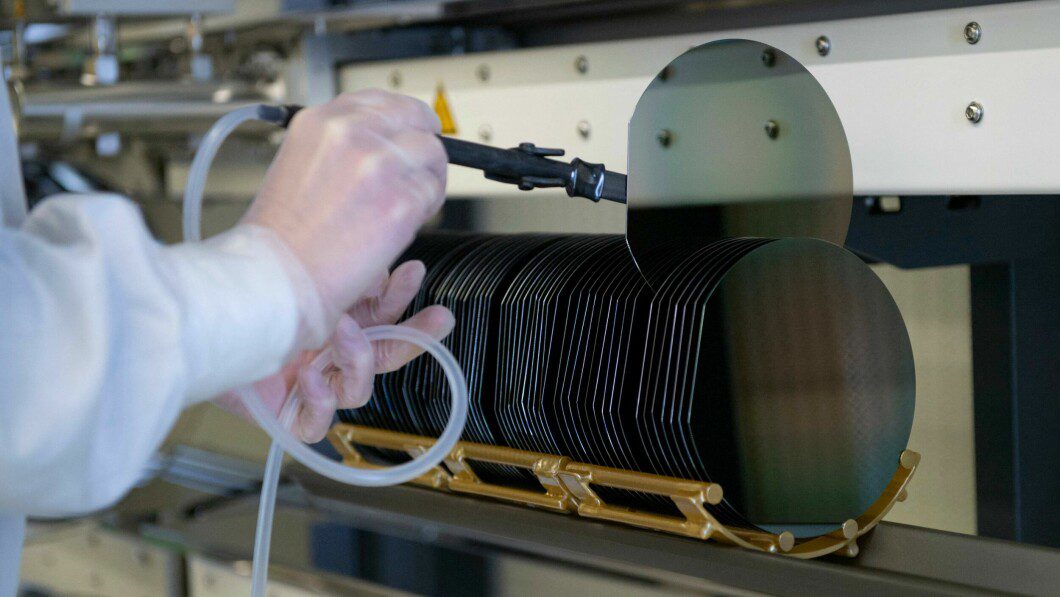

As if all the mentioned problems weren’t enough, the actual manufacturing of microchips is a tedious process.

in Article from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)describes how to implement a 14-week production process with 700 steps to make so-called silicon wafers, which are an essential part of microchips.

Spends a lot of time waiting for the crystals to grow.

– It’s physics. One cannot increase the frequency of this. You can hire more people, buy more equipment, but if you don’t have the materials to make the final product, you’re not getting anywhere, says Jessica Kelly of National Instruments (NI).

This is what it looks like when you take out a silicon wafer for microchip production. This image is from the Institute of Microelectronics of Barcelona (IMB-CNM). Photo: JOSEP LAGO / AFP

minor irritation

The rescue for lead student Berger Olsen was to order chips from the remaining stock to three different suppliers in different parts of the world.

Many of the world’s semiconductors are manufactured in Asia and the Taiwanese company TSMC, but the United States is also a major supplier.

Some suppliers only had ten chips left in stock. In the end, there were three different orders, so there was a bit of annoyance with the management in the university, heh.

Said: Masters student Berger Olsen (24) eventually finished, but due to the shortage, the process became more exciting than it should have been. Photo: Silje Olderkjær / TV 2

He was, of course, “happy.”

Fortunately, Olsen eventually finished. The microchips arrived in Bergen, and his part of the project was completed.

At the end of June, he submitted his master’s thesis, which he naturally thought was delicious.

– Yes, I was obviously “happy” for that. It was a relief to have the circuit board produced and get to the point where you can test it.

Then you will see if next year’s students in microelectronics will get easier.

“Web specialist. Lifelong zombie maven. Coffee ninja. Hipster-friendly analyst.”